The COVID-19 pandemic is playing out in very different ways across the country and state by state. This is also true in Tennessee, according to a new analysis by faculty researchers at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

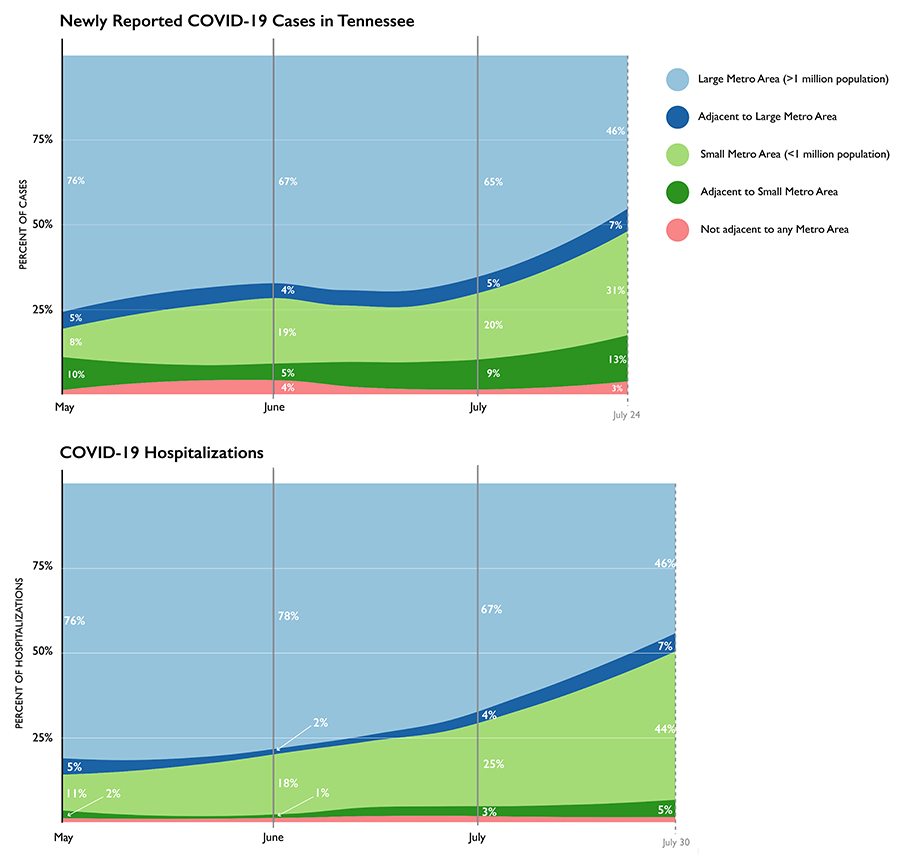

What was initially an outbreak concentrated in large urban areas has moved into more rural communities with fewer health care resources. In Tennessee, more than half of newly reported cases of COVID-19 and hospitalizations are now in areas outside of the state’s two largest metro areas, Nashville and Memphis.

By contrast, early in the pandemic, more than three-quarters of cases and hospitalizations were located in the two largest metropolitan areas. Many of the state’s regions were on similar rising trajectories, but since mid-July the experience of these regions has begun to diverge.

Understanding this shift is critical for targeting resources and preparing to address increasing needs for services and effects on rural health care systems, said John Graves, PhD, associate professor of Health Policy and director of the Center for Health Economic Modeling.

As a largely rural state, Tennessee stands to be among the states most affected by this shift, researchers said.

“It could even be that hospitalization estimates are understating the burden the smaller and more rural areas of the state are facing because some patients from these areas are being treated in facilities in larger metro areas,” Graves said.

“That makes it even more important for health care leaders and public officials to closely monitor these trends to best deploy its resources and mitigation strategies.”

On May 1, 11% of hospitalized patients were in facilities located in small metro areas with populations less than 1 million people. By late July, hospitals in small metro areas were treating 44% of hospitalized patients statewide.

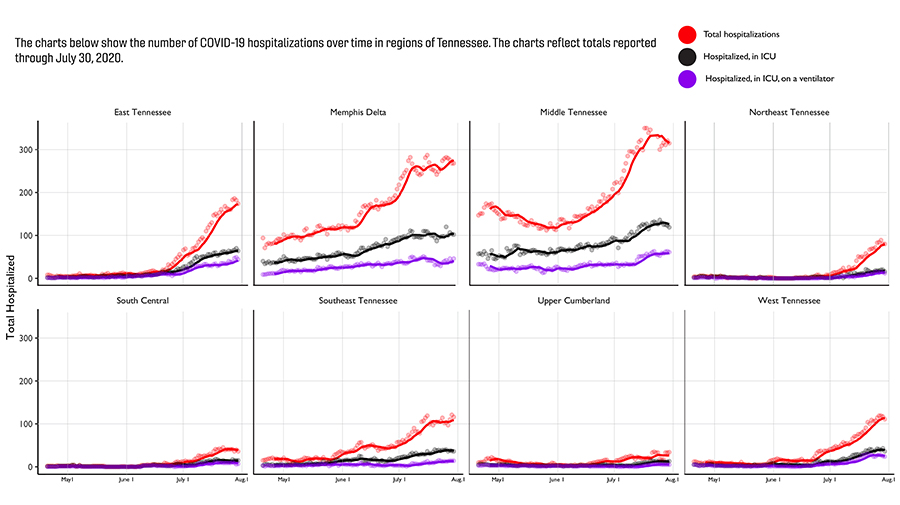

Hospitalizations remained on an upward trajectory through the end of July in many of these smaller areas, according to the analysis. In Nashville, Memphis, and Chattanooga however, hospitalizations had shown signs of stabilizing.

“Of course, stability over a period of a month or less does not imply that cases and hospitalizations will not go up — or down — in the coming months,” said Melinda Buntin, PhD, Mike Curb Professor of Health Policy and chair, Department of Health Policy.