Tennessee areas where mask requirements were instituted over the summer have substantially lower death rates due to COVID-19 as compared to areas without mask requirements, according to a new analysis by Vanderbilt Department of Health Policy researchers.

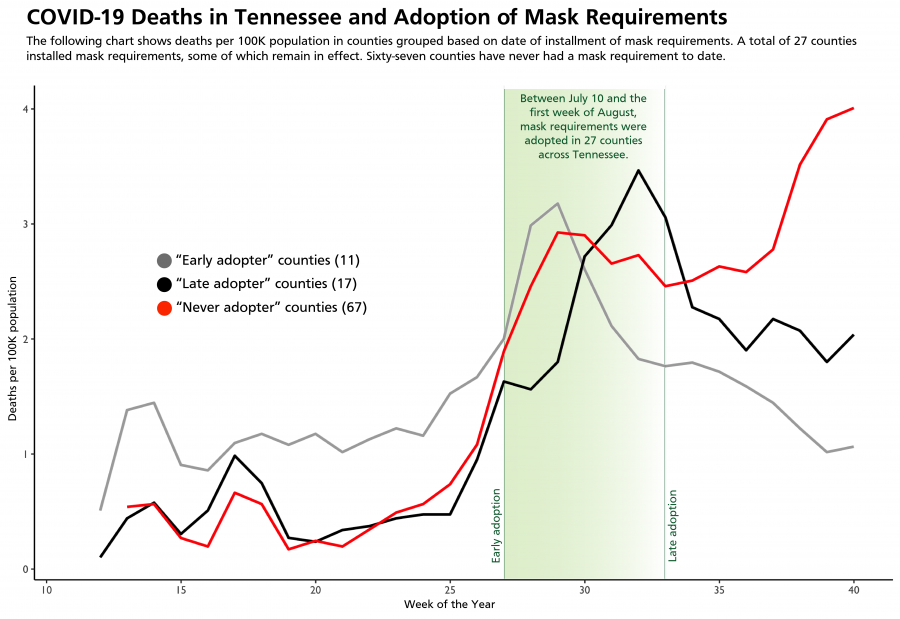

The analysis, led by John Graves, PhD, associate professor of Health Policy and director of the Vanderbilt Center for Health Economic Modeling, finds that early adopting counties saw their death rate begin to decline by late July, while later adopting counties saw declines in August and September. Non-adopting counties continue to see death rates rise, the researchers found.

“This analysis shows that strategies, including but not limited to masking while in contact with others, can have real impact on people’s lives,” Graves said. “Mask mandates are associated with greater mask wearing and other behaviors like limiting close contacts with others, and the combined impact is clear and substantial.”

The study uses data on COVID-19 deaths by date of death, which is earlier than reported by the state, up to Oct. 1. The analysis reflects deaths that were tied to infections in mid- to late September, before the recent surge in cases of COVID-19 in Tennessee.

The analysis expands on other analyses that Graves, along with Melinda Buntin, PhD, Mike Curb Chair of the Department of Health Policy, and Melissa McPheeters, PhD, MPH, research professor of Health Policy and Biomedical Informatics, have conducted about the implementation of mask requirements and hospitalizations.

Due to changes in masking mandates, as of Nov. 10 approximately 63% of Tennessee residents lived in areas where a mask was required, while the remaining 37% lived in an area where masks were never required (8%) or lived in areas where mask requirements expired.

Death rates were initially higher in the areas where masks became required, the analysis found. In the weeks after mask requirements were put in place, areas where masks were required showed sharper declines in deaths per 100,000 population compared to areas where masks were never required.

“Deaths are a lagging indicator, following increases in cases and then hospitalizations, so we expect any intervention such as a mask requirement to take some time to demonstrate effectiveness. Rising rates of COVID-19 are a big ship to turn, and it is important to act early enough to be effective,” McPheeters said.

“As of the first week of October, there were more than four deaths per 100,000 population in areas where masks were never required and near or below two deaths per 100,000 in areas that adopted a mask requirement over the summer,” Buntin said.

The good news, researchers noted, is that more than 80% of Tennesseans were reporting as of Nov. 5 that they are wearing masks, according to research cited in the analysis from Carnegie Mellon University. The analysis notes, however, that mask wearing may be inconsistent, especially when around close family and personal contacts.

“Individuals may not understand the risk of exposure to friends and family and may ‘let down their guard’ in situations where they are meeting in small groups with close contacts,” the researchers concluded. “Mask ordinances demonstrate leadership by sending a clear signal that behavior must change to mitigate spread of the virus.”