A new study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy evaluates the effect of a Tennessee law that went into effect in 2013 aimed at reducing the supply of opioids prescribed.

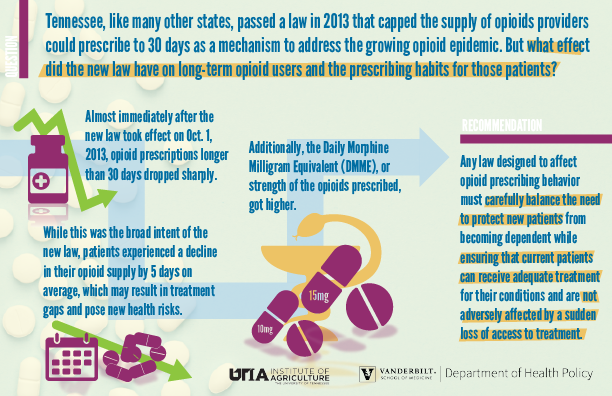

The law itself was one of many similar laws that were passed by states to address the growing opioid epidemic. Tennessee’s law limited the days supply of opioids that could be prescribed in a single prescription to 30 days. The law worked in that sense, the study found. The number of prescriptions with more than a 30-day supply dropped sharply as the law took effect, and continued to decline slowly through 2014.

On average, after the law took effect, patients received 5 fewer days’ worth of opioids in a month. The researchers note that patients who were receiving long term opioid treatment could face health risks if this drop in days’ supply resulted in a treatment gap.

“There’s obviously the risk that patients endure unmanaged pain for that period, but there’s also a risk that some patients will try to find relief through other means,” said McPheeters. “Reduced access to necessary treatment can be dangerous. Unfortunately, this research does not give us clear insight into whether these types of gaps occurred; but it does raise the question.”

The data also sheds light on how providers compensated for the change in the law. While most followed the new prescribing rule, the data found that the Daily Morphine Medical Equivalent, or the dosage strength, increased. In other words, possibly to compensate for the reduced supply, some providers prescribed stronger opioids.

The study recommends that policy makers and future research consider this particular population in future endeavors.

“Any law designed to affect opioid prescribing behavior must carefully balance the need to protect new patients from becoming dependent while ensuring that current patients can receive adequate treatment for their conditions and are not adversely affected by a sudden loss of access to treatment,” the study said.

The study was partly funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which did not have input into the research.

It publishes in the March 2020 edition of the journal.