Learn how to identify the type of feeding assistance most likely to increase an individual resident’s food and fluid intake. Use our Mealtime Feeding Assistance Protocol and our Between Meal Snack Protocol to guide this evaluation process.

Click on one of the following topics or proceed to Step 3.

-

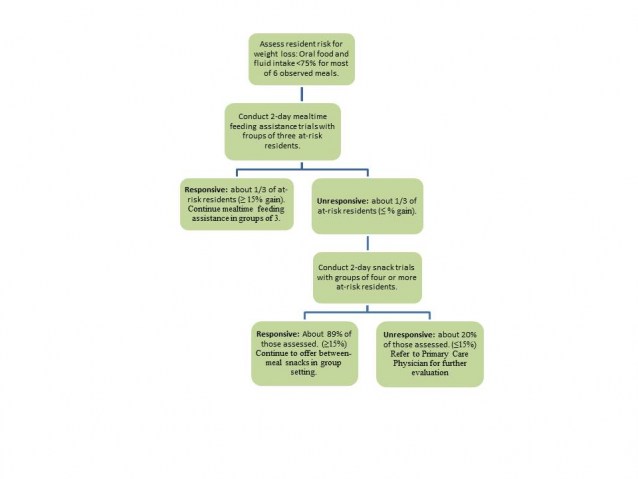

Findings from our most recent research suggest that it is possible to improve feeding assistance and increase food and fluid intake among residents without hiring more staff. The key to success is using existing staff more efficiently and creatively. To do that, however, nursing home staff must first determine which of two possible feeding assistance interventions works best for residents who typically under eat.

Over the years, we’ve worked in numerous nursing homes and not one of them, without considerable urging from us, has ever assessed nutritionally at-risk residents to determine whether in fact they would eat more if offered proper feeding assistance. Staff fore go these assessments largely because they believe they’re unnecessary: There’s a strong assumption bordering on faith that more and better feeding assistance will inevitably prompt poor eaters to consume more. This belief is at the heart of the Bush Administration’s recent rule change allowing part-time “feeding assistants” to help residents during busy mealtimes. The idea is that more workers equals more feeding assistance, which in turn equals greater food and fluid intake among residents who would otherwise under eat.

The problem with this equation is that it doesn't add up to success for a lot of residents at risk for under-nutrition. Our studies show that not all residents respond equally well to mealtime feeding assistance; in fact, only about half of residents who typically under eat will increase their intake of food and fluids when offered high quality feeding assistance at mealtimes (1). Most “unresponsive” residents, however, will eat more when offered between-meal snacks (2).

These findings underscore the need to individualize feeding assistance in nursing homes; one size, it turns out, does not fit all. Failure to determine which intervention—mealtime or snack—works best for which resident can lead to costly staff inefficiencies and poor clinical outcomes for residents. Nurse aides waste time trying to feed residents who are unlikely to respond to their help. Meantime, these residents remain at risk for under-nutrition and weight loss because they don’t get the assistance and snacks between meals that they really need.

-

On the flip side, these findings point to new, more efficient and creative ways to deploy staff for maximum benefit. We discuss staffing options in more detail in Step 3. Here it’s worth noting that our dual-component intervention frees nurse aides from having to provide intensive feeding assistance to all at-risk residents at mealtimes. It also opens the door to appointing other staff members, most notably social activities personnel, to deliver snacks to at-risk residents between meals.

Before reassigning staff, however, you must assess residents’ responsiveness to the mealtime intervention and, if necessary, the snack intervention. Only then are certain staffing structures ethically and clinically justifiable.

-

Simple Strategy Identifies Responsive Residents

Is there, in fact, a reliable method for accurately identifying which residents will eat more if offered adequate help at mealtimes? Yes. It’s an assessment method that we’ve used successfully in other care areas (see our training modules on incontinence management—link to imcontents and mobility decline prevention—link to mdcontents) and one we found works equally well with feeding assistance. It’s a simple method based on common sense: Offer at-risk residents ample feeding assistance for a few days and monitor their food and fluid intake. Those who eat more as a result of the intervention are “responsive” to it; those who don’t are “unresponsive.” In other words, the intervention either works, or it doesn't, and there’s no reason to expect its effect to alter unless there is a significant, unrelated change—for better or worse—in the resident’s condition. This same strategy also works to identify residents who respond well to the snack intervention.

A WORD OF WARNING: Don’t, as so many nursing home staff do, use a resident’s cognitive status to assess responsiveness to this or most other daily care interventions (e.g., scheduled toileting assistance). Time and again, we have found that residents with severe cognitive impairment are nevertheless responsive to these behavioral interventions (1, 3, 4).

-

A mealtime feeding assistance trial can be accomplished in two days (six meals), and any resident who eats less than 75% of most meals (see Step 1: Resident Assessment) should undergo this further assessment.

As a practical matter, the two-day feeding assistance trial should be conducted with groups of three residents. Our research shows that most residents who increase their intake in response to one-on-one feeding assistance maintain that increase when the help is provided in small groups of three (1). All residents should be medically stable at the time of assessment.

A nurse or nurse aide should provide continuous feeding assistance to the group for a total of six meals, preferably breakfast, lunch, and dinner, on two days within the same week. Be forewarned: This critical assessment step requires considerable staff time to complete. Plan on spending about 45 minutes per meal to assess a group of three residents and another 10-12 minutes per resident if a snack-intervention assessment is required. But take heart: These are one-time assessments for most residents. Finish them and your staff can move on.

Staff should follow procedures in our Mealtime Feeding Assistance Protocol to conduct the two-day trial. Briefly, the intervention protocol calls for the following:

- The staff person should casually converse or otherwise socially interact with the residents throughout the meal.

- Residents should be properly positioned to eat – sitting upright.

- Residents should have their dentures, glasses, and hearing aides, if needed.

- Resident requests for substitute food and fluid items should be honored (and substitutes should be offered by staff if a resident doesn’t seem to like the served meal). If a resident entirely consumes a particular food or beverage, offer a second helping, even if the food is a dessert. Most experts agree that the primary goal here is to increase caloric intake for residents at risk of weight loss. It is helpful to coordinate the availability of substitutions and second helpings with the kitchen staff such that these items (e.g., sandwiches, fruit plates, desserts) are available on the unit and do not require the staff member providing feeding assistance to leave the residents they are helping and make a trip to the kitchen.

- Residents should have access to their trays for up to 1 hour per meal (the average is about 45 minutes and the minimum is 30 minutes). Feeding assistance ends when the resident has refused all food and fluid items on his or her tray multiple times.

- An oral liquid nutrition supplement should be offered to residents at the end of the meal and only if they have refused all other food and fluid items on their tray as well as offers of substitutions, have consumed less than 75% of their meal, or have verbally requested a supplement.

The nurse or nurse aide should follow our graduated prompting protocol to encourage residents to feed themselves. This standardized procedure instructs staff members to try simply tray set-up and verbal prompts to encourage residents to eat before offering physical guidance or assistance. This protocol also allows staff to determine each resident’s true feeding assistance care needs and can be used as a standardized way to complete the MDS eating dependency item (Section G. Physical Functioning. Item 1h). The levels of assistance are as follows:

Graduated - Prompted Protocol: Levels of Assistance

-

social stimulation and encouragement

-

tray set-up (e.g., rearrangement of items on tray for easy accessibility; opening containers; offering to put sugar in tea, butter on bread, salt and pepper on foods, cutting up meat)

-

verbal cueing (e.g., “Why don’t you try some of your soup?”)

-

physical guidance (e.g., assist resident in holding cup or utensils, placing bite of food on fork for resident to then pick up and feed self and guiding resident’s hand to the utensil to initiate self-feeding)

-

full physical assistance (staff member physically feeds resident)

NOTE: Each level of assistance is embedded within successive levels such that level 5 includes all previous levels. For example, staff should continue to provide social stimulation; orient the resident to the meal, food, and fluid items being served; and provide physical guidance, if at all possible, in the context of full physical assistance. In addition, some residents require full physical assistance for food items but remain capable of holding their own cup, with physical guidance.

Taken together, these intervention components enhance independence, support individual preferences, and characterize optimal feeding assistance quality, according to multiple experts (5-9).

Our Mealtime Feeding Assistance Protocol also instructs staff members to record the following:

- How much each resident ate during the meal (total percentage consumed)

- How long staff spent providing assistance during the meal

- The type of assistance the resident needed to encourage intake and enhance independence in eating

This information is used to determine the intervention’s effectiveness and later, to organize staff efficiently (see Step 3 and our nutrition software link).

-

To determine a resident’s responsive to the mealtime intervention, simply compare the resident’s average intake during the two-day trial to his or her average intake during the Step 1: assessment

Residents are considered responsive if they show at least a 15% gain in average total consumption (1, 2).

If the resident’s intake information under the two conditions (Step 1 assessment and the two-day trial of assistance) is entered into our nutrition software program, a report can be generated that summarizes the resident’s responsiveness status. This report can be used as medical record documentation of a feeding assistance trial, which is consistent with federal care practice guidelines for nutrition.

All responsive residents should continue to receive the feeding assistance intervention at all mealtimes daily in small groups of three. All others—an estimated 50% of residents with low intake—should be assessed for responsiveness to the snack intervention, presented below. At the staff’s discretion, the mealtime feeding assistance intervention can be discontinued for these “non-responsive” residents.

DOUBLE-DUTY ASSESSMENT: Our mealtime intervention protocol can be used as an educational tool during in-service training sessions to teach nurse aides and other workers, such as supplementary “feeding assistants”, how to provide high-quality feeding assistance.

TIME-SAVING TIPS: Group together residents with similar assistance needs during meals in order to facilitate efficient delivery of feeding assistance and allocation of staff based on residents’ needs (e.g., full physical assistance versus social stimulation and verbal cueing alone). Alternatively, you may want to include a combination of 1-2 residents who require full physical assistance to eat with 1-2 residents who require only social stimulation and verbal cueing. This way, the staff member can cue one resident while physically helping another.

Residents who are bed-bound or who refuse to come to the dining room for meals (to allow group feeding assistance to occur) may be assessed for responsiveness to the snack intervention.

If the facility houses a large proportion of residents who eat less than 75% of most meals, mealtime feeding assistance trials can be targeted toward residents at particularly high risk for weight loss based on other criteria, such as: eats less than 50% of most meals, history of or recent weight loss episode, or Body Mass Index below 21. The MDS criterion “leaves 25% or more of food uneaten” will capture some residents who do not, in fact, need intervention especially if a facility serves a lot more than 2000 calories/day during regularly-scheduled meals.

-

- All residents who are not responsive to the mealtime intervention should receive a two-day trial of a between-meal snack intervention. Staff should follow procedures in our Between Meal Snack Protocol to conduct this assessment trial. This protocol is similar to that used for mealtime feeding assistance:

- Staff should offer snack foods and fluids to groups of four residents three times per day between meals (typically at 10am, 2pm and 7pm) for about 15-20 minutes per snack period, per group of residents.

- Staff should offer a variety of foods and fluids that the residents can choose from during each snack period. If possible, present snacks on a moveable, attractive cart so that residents can see their choices. Much like the dessert cart at a restaurant, the visual stimulation may stir the appetite. Recommended snacks include assorted juices (apple, cran-apple, cran-grape), yogurts (whole milk yogurts are more calorie-dense, creamier and tastier to the residents), ice cream, fresh fruit (bananas, apple slices), puddings, applesauce, soft cookies, pastries (mini muffins), cheese/peanut butter, and crackers. Oral supplements as well as snacks appropriate for diabetics and others on special diets should be provided as needed.

- Staff should follow our graduated prompting protocol (please bookmark to appropriate section above) to encourage residents to feed themselves.

- The staff person should casually converse or otherwise socially interact with the resident throughout the snack period.

- Residents should be properly positioned to eat.

Throughout this two-day trial, staff must monitor participating residents’ food and fluid intake at each meal (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) in order to determine if the calories gained from snacks result in lower intake of meals. Use our Mealtime Observational Protocol to conduct these assessments.

- Similar to the mealtime protocol, the snack protocol instructs staff members to record the following:

- How much of each item the resident ate or drank during the snack period

- How long staff spent providing assistance during the snack period

- The type of assistance the resident needed to encourage intake and enhance independence in eating

-

Follow these procedures to determine a resident’s responsiveness to the snack intervention:

- Calculate the resident’s average daily total calories consumed during the two-day trial (count all meals plus snacks).

- Compare this total to the resident’s average daily intake as determined in the Step 1 assessment.

- Residents are considered responsive if they show at least a 15% gain in average daily calories or an increase of 300 or more calories a day (2).

Another easy way to calculate responsiveness without a lot of math is as follows:

- Compare the resident’s average total percent eaten during meals when snacks are being given to their average total percent eaten during meals as determined in the Step 1 assessment. If these two average values are comparable (less than 15% difference), then meal intake is essentially unchanged by snack delivery.

- The resident should accept at least 2 of the 3 daily snack offers. If their refusal rate is higher than once/day for snacks, they are likely not a good candidate for snacks (OR, the staff is not doing a good job of offering them choices during the evaluation).

- The resident should consume approximately 100 to 150 calories per snack offer (e.g., 4-6 oz of juice and 1 serving of yogurt). If the resident is accepted at least one fluid and one food item per snack offer, s/he is likely a good candidate for snacks.

Our nutrition software program can determine residents’ responsiveness to the snack intervention if you enter each resident’s food and fluid intake estimates for each condition: the Step 1 assessment and the two-day trial of snacks.

Responsive residents should continue to receive the snack intervention daily – ideally, three times per day but a minimum of twice per day. It is possible to examine which times of day residents within the facility seem most responsive to snack delivery. In our previous work, the morning and afternoon snacks resulted in higher caloric intake relative to the evening snack period.Our research indicates that about 80% of the residents who receive the snack intervention will prove responsive to it (2). Moreover, our research also has shown that offering residents a choice of snack foods and fluids at least twice daily is a more cost-effective intervention than the use of oral liquid nutrition supplements in that snacks result in higher gains in caloric intake, lower refusal rates, and less staff time to promote consumption. In short, most residents prefer snacks to supplements (10). Finally, we also have demonstrated that the provision of optimal mealtime feeding assistance or snack delivery at least twice daily, five days per week (using the assessment protocols we describe in this module) results in significant improvements in residents’ daily food and fluid intake and body weight status over time (11). In short, these interventions really do work to improve nutrition and hydration status and prevent unintentional weight loss among at-risk residents.Once you have determined who is responsive to either the mealtime intervention or the snack intervention you can re-deploy staff to achieve the maximum benefit for residents in the most time-efficient manner (move on to Step 3 or use our nutrition software to project staffing needs).

Residents who prove to be unresponsive to both interventions (anticipated 10% or so of those who meet the MDS criterion for “low intake”) should receive a follow-up evaluation from their primary care physician and consultation with respective family members, if appropriate. For these residents, a two-day trial of mealtime feeding assistance and between-meal snacks provide the nursing home staff with important medical record documentation consistent with federal care practice guidelines related to nutrition that these interventions were attempted in an effort to prevent unintentional weight loss.

DOUBLE-DUTY ASSESSMENTS: The two days of assessment for the mealtime and snack interventions are an opportune time to collect, with almost no extra effort, additional information required on the MDS and critical to improving nutritional care. For each resident assessed, consider recording this information:

- Symptoms of mood disturbance (e.g., repetitive health complaints, negative self-statements, crying or tearfulness)

- Behavioral problems that interfere with eating or the provision of feeding assistance (e.g., agitation, resident refusal of food or staff assistance)

- Need for assistive devices during meals (large-handled utensils, plate guards)

- Evidence of swallowing or chewing difficulties, including problems with dentures

- Food preferences and complaints

Use the information you collect to further individualize feeding assistance for at-risk residents.