A new Vanderbilt study is the first to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to noninvasively measure lymphatic flow. Researchers say this technique holds future potential in the identification of patients at highest risk for developing lymphedema and in the evaluation of response to lymphedema therapy.

The lymphatic system is a network of vessels and nodes carrying protein-rich fluid and functions as the body’s waste filtration system. Lymphedema is a chronic condition that occurs when this system is unable to adequately drain the fluid. The fluid retention, most notable in the arm or leg, can cause swelling, pain and impaired mobility.

Lymphedema is most common in patients following surgeries that involve lymph node removal or radiation therapy. An estimated 19 percent to 49 percent of breast cancer patients with lymph node removal develop lymphedema, with some studies suggesting an even higher incidence.

“The risk of developing lymphedema is lifelong. The problem is we don’t have a way of predicting who will get lymphedema and how soon they will develop it. As clinicians, we can only provide generic prevention education and react once it happens,” said Paula Donahue, DPT, a certified lymphedema therapist at the Vanderbilt Dayani Center for Health and Wellness and faculty member in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R), and co-author of the study.

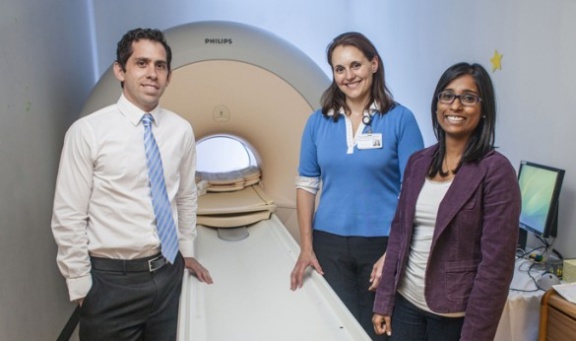

Her husband, Manus Donahue, Ph.D., assistant professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences with the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science (VUIIS), happens to be an expert in visualizing and measuring blood flow. One day she asked if he could apply the technique to the lymphatic system and the research study was born.

With collaboration from Swati Rane, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow in Radiology at the VUIIS, and assistance from Ted Towse, Ph.D., assistant professor of PM&R, and Sheila Ridner, Ph.D., MSN, professor of Nursing, the researchers validated that spin labeling, long used to measure blood flow, could be adopted to measure lymphatic flow.

“What’s interesting is that many MRI properties of lymph have never been published. MRI and spin labeling have been around for so many years, but never used in lymph. We were starting from scratch,” said Rane, who won the summa cum laude merit award from the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine for this research.

In the first part of the study, the researchers used donor lymph fluid to validate their spin labeling technique. Spin labeling changes the magnetic properties of water molecules in a fluid, making them trackable by MRI.

“It’s analogous to injecting a contrast agent, but instead we’re just changing the magnetic properties of the water protons. It’s totally safe and doesn’t have the contraindications that radioactive tracers have,” said Manus Donahue. “Lymph vessels are also much thinner and have different integrity than blood vessels, and injecting a contrast agent fundamentally changes the fluid transport properties. Therefore being able to do this noninvasively with MRI is really important.”

Next, researchers tested six healthy volunteers to assess whether the in vivo spin labeling matched expected flow velocities. Conditions of lymphedema were simulated using a blood pressure cuff to temporarily slow lymph flow in one arm of the healthy volunteers. Then the method was applied to measure lymph flow in patients with lymphedema.

In healthy subjects in the unaffected arm, the flow rate was approximately 0.6 cm per minute. It reduced to 0.5 cm per minute in the cuffed arm. Such subtle but significant decreases in lymphatic flow, consistent with lymphedema, were captured with this new approach. Lymphedema patients showed a similar reduction in the lymph velocity in the affected arm to 0.5 cm per minute.

“We hope this will be directly transferable to our clinical practice to evaluate our current lymphedema therapies and help identify biomarkers that may help patients understand their individual risk and whether they need to be aggressive with prevention strategies,” said Paula Donahue.

The technique may also help determine which lymph nodes carry the highest lymphatic burden and guide surgical decisions, possibly reducing lymphedema incidence further.

“Usually when you do research you contribute your small piece to the puzzle and hopefully move the field incrementally forward. But this, I think, has the potential to create a new imaging field and bring attention to an understudied area,” Manus Donahue said.

The study, “Clinical Feasibility of Noninvasive Visualization of Lymphatic Flow with Principles of Spin Labeling MR Imaging: Implications for Lymphedema Assessment,” was published online in the journal Radiology and recently accepted for print publication.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NINDS 5R01NS078828-02).